The art table

Working on the ‘art table’ at OHF involved taking paper and drawing materials from the art cupboard and sitting down at one of the long tressle tables in the main hall. Here young men, ninety five percent of them Afghans, sit to play cards, converse and play on their mobile phones. Most are aged from their late teens to mid twenties; a handful are older. (Sometimes a group of four middle aged men would sit together, playing cards. They had weather-beaten, handsome faces and reminded me of Cezanne’s card players.)

I would sit down at a table with some space, spread out my stuff and start drawing or making a collage. Very loud music, constant movement in the hall, the buzz of conversation and my lack of Farsi made it impossible to explain a structured project of any kind. But most days, within half an hour there would be a few people drawing around me. Sometimes people would come up and watch what I was doing for a few minutes. I dealt with the excruciating noise by becoming very focused on my drawing; but eventually I’d look up, ask them if they wanted to draw and if they nodded, I gave them a sheet of paper and one of my Faber Castell pencils. Some sat down and gazed around uncomfortably, unsure where to start; others immediately searched for an image on their phones, usually a photo of a face which they liked, and started to copy it.

The first days few days I brought in lemons and an orange from the citrus grove by my place. I laid them out on a sheet of coloured paper with a sprig of olive leaves and a rubber tree leaf picked on the way into Mytilini. I drew them, and enjoyed it; but very few of the refugees took up the idea. One or two would pick up the orange and pretend to be about to sink their teeth into it. Then it dawned on me that they have a poor diet at Moria and the sight of fresh fruit might be difficult.

Sometimes half way through the morning, one or two women would come and join us. I was always pleased. And towards lunch time children would appear. The idea was that anybody and everybody should be given materials if they showed interest; it was, as one of the long term volunteers put it, an ‘open space’.

Two images appeared regularly in the drawings that were produced. One, a curious bird, a bit like a peacock, with a large breast and a long tail. I imagine it’s some symbol of Afghanistan. The other was a very stylized, curling stem of leaves with flowers attached, spread at regular intervals along the stem. People would spend up to two hours colouring in the petals bright red and the stem a uniform green.

To me the most interesting piece of work was done by a man with a bony, intelligent face, who came several times and communicated to me that he was intent on learning to draw better. He had a wonderful smile and would work for hours in silence, very focused despite the hubbub going on around him. One day he did a very small drawing of a house in the middle of a spacious, scrubby landscape. The next day I got out some paints and he drew and painted what he said was the camp at Moria, with the olive groves around it. He showed me a google earth image of the camp on his phone; his painting closely mirrored it.

In general the children speak English better than the adults. A boy of about ten carefully drew and coloured a sign saying ‘MORIA, NO GOOD’.

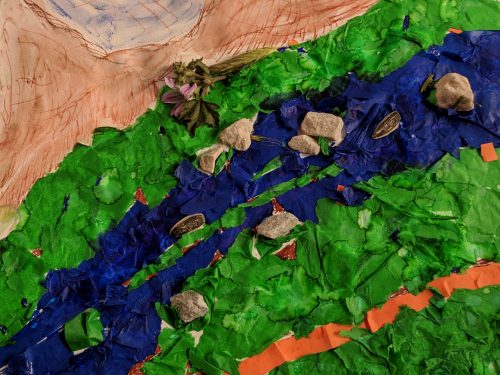

Collage must have seemed a very odd idea as very few people did it. I was having a lovely time making collages of the sea and the Turkish coastline – we had red, blue and green tissue paper only – and people would sometimes watch with interest but mostly not want to join in. One man, however, a young dad of about twenty, made a wonderful three dimensional collage, with pieces of stone and a flower attached.

When people had finished their drawings, they would either leave them on the table and walk away, or hand them to me. I tried to suggest that they keep their work, but nobody wanted to. After a few days I was given some blutak and started putting work up on the walls.